by

Brendon Baillod

One of the most interesting and historic military sites connected with Wisconsin is the September 8, 1860 wreck of the steamer Lady Elgin. Although she actually lies in Illinois waters, her role in Wisconsin history is both substantial and tragic. The May 1989 discovery of some of her remains off Highwood, Illinois by Chicago salvor Harry Zych has rekindled interest in the wreck and subsequent court battles over salvage rights have kept the Lady Elgin in the news periodically. In the spring of 1995 the Elgin's remains were placed on the National Register of Historic Places and her notoriety continues to grow. The Lady Elgin held the dubious distinction of being the worst loss of life on the Great Lakes until the steamer Eastland rolled over at her Chicago dock in 1915 killing 835, and the Elgin still ranks as the second worst wreck in the history of the Lakes. With the increasing popularity of sport diving, the Elgin's remains have now become a popular underwater attraction and she is the subject of ongoing archeological investigation.

Often overlooked, is the Lady Elgin's role in Wisconsin's Civil War politics and the furor her loss produced. In 1860, Wisconsin was embroiled in the debates over states' rights fueled by the slavery question. The nation nervously awaited the results of the 1860 presidential election which would decide the country's direction on many issues. In Wisconsin there was much anti-slavery feeling. So much so, that one Waukesha legislator even introduced a motion directing Wisconsin to declare war against the United States unless the Federal Government abolished slavery. Wisconsin's Republican governor, Alexander Randall was also a staunch abolitionist and a strong advocate of states' rights. He had previously suggested that Wisconsin would secede from the Union if the Federal Government did not end slavery.

When

Wisconsin's secession began to look like a possibility, the State Adjutant General

surveyed all the State's militia companies to determine which would support

the State and which would support the Federal Government in such an event. Milwaukee

hosted four main militias; the German Green Jagers, the German Black Jagers,

the Milwaukee Light Guard and the Irish Union Guard of Milwaukee's Third Ward.

When the question was posed to Captain Garrett Barry, the commander of Milwaukee's

Union Guard and a Democrat, he replied that while he was opposed to slavery,

he considered any stand against the Federal Government to be treason. When news

of Barry's response reached the Adjutant, he promptly revoked Barry's militia

commission and disarmed the Union Guards. Barry and his Guards were incensed.

They refused to disband and determined to raise money to rearm their proud unit.

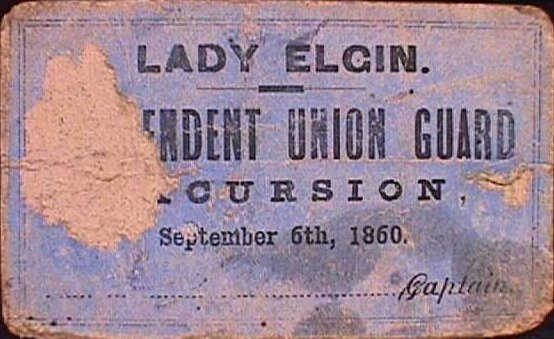

With the help of the local Democratic Party, they decided to commission an excursion

to raise money and lift political spirits. They booked passage for their Company

and guests on the Lady Elgin for a cruise to a Democratic party rally in Chicago

where they would go on parade and hear a speech by Illinois Congressman and

presidential candidate Stephen A. Douglas.

When

Wisconsin's secession began to look like a possibility, the State Adjutant General

surveyed all the State's militia companies to determine which would support

the State and which would support the Federal Government in such an event. Milwaukee

hosted four main militias; the German Green Jagers, the German Black Jagers,

the Milwaukee Light Guard and the Irish Union Guard of Milwaukee's Third Ward.

When the question was posed to Captain Garrett Barry, the commander of Milwaukee's

Union Guard and a Democrat, he replied that while he was opposed to slavery,

he considered any stand against the Federal Government to be treason. When news

of Barry's response reached the Adjutant, he promptly revoked Barry's militia

commission and disarmed the Union Guards. Barry and his Guards were incensed.

They refused to disband and determined to raise money to rearm their proud unit.

With the help of the local Democratic Party, they decided to commission an excursion

to raise money and lift political spirits. They booked passage for their Company

and guests on the Lady Elgin for a cruise to a Democratic party rally in Chicago

where they would go on parade and hear a speech by Illinois Congressman and

presidential candidate Stephen A. Douglas.

The

excursion left Milwaukee in the early morning hours of September 7th, 1860 and

arrived at Chicago by dawn. That morning the unit went on parade before many

spectators and then toured the city. In the evening, they attended a dinner-dance

and heard the Senator's oration. By 11:00 PM the Guards were ready to leave,

but Captain Jack Wilson of the Lady Elgin was concerned about the weather. Wilson

was a veteran lakes captain who knew the lake could be treacherous in September,

but the eager passengers and pressure to maintain a federal mail schedule convinced

him to get underway. Several new passenger were taken on board and around 11:30

the Elgin cleared Chicago Harbor and headed out into the open lake. Reports

vary, but contemporary accounts and subsequent lists suggest that between 600

and 700 persons were aboard when the Lady Elgin departed. Many excursionists

turned in for the night, exhausted from their busy day, while other guests danced

and reveled in the Elgin's spacious salons. The Elgin left with little warning,

reportedly departing before a number of unticketed visitors had a chance to

disembark. Within a few hours the winds had increased to gale force and a high

sea was running but the Elgin was weathering the storm well.

The

excursion left Milwaukee in the early morning hours of September 7th, 1860 and

arrived at Chicago by dawn. That morning the unit went on parade before many

spectators and then toured the city. In the evening, they attended a dinner-dance

and heard the Senator's oration. By 11:00 PM the Guards were ready to leave,

but Captain Jack Wilson of the Lady Elgin was concerned about the weather. Wilson

was a veteran lakes captain who knew the lake could be treacherous in September,

but the eager passengers and pressure to maintain a federal mail schedule convinced

him to get underway. Several new passenger were taken on board and around 11:30

the Elgin cleared Chicago Harbor and headed out into the open lake. Reports

vary, but contemporary accounts and subsequent lists suggest that between 600

and 700 persons were aboard when the Lady Elgin departed. Many excursionists

turned in for the night, exhausted from their busy day, while other guests danced

and reveled in the Elgin's spacious salons. The Elgin left with little warning,

reportedly departing before a number of unticketed visitors had a chance to

disembark. Within a few hours the winds had increased to gale force and a high

sea was running but the Elgin was weathering the storm well.

By 2:30 AM the Lady Elgin was about seven miles off Winnetka, Illinois when a tremendous jar was felt throughout the ship and she suddenly lurched onto her port side. Passengers who had been looking out the portholes reported seeing the lights of a vessel rapidly approaching the Elgin and braced for a collision. When the collision came, most of the Lady Elgin's oil lamps went out creating an air of confusion on board. Captain Wilson and First Mate George Davis had been asleep in their state rooms and dressed hurriedly. Captain Wilson went below and found a massive amount of water entering the engine room, while First Mate Davis rushed to the pilot house and ordered the Elgin turned toward shore. When Captain Wilson returned to the pilot house he privately told the mate that the Elgin would never reach shore.

The vessel that had inflicted the damage was the 129 ft., 266 ton schooner Augusta. She was a two masted vessel bound for Chicago with a deckload of lumber. Despite the gale, she was still flying most of her canvas and was sailing out of control. As she shot through the water, her deckload had shifted and she was nearly sailing on her side. The Augusta was in danger of capsizing and her crew was fighting to regain control of her. Her mate, John Vorce had sighted the Lady Elgin's lights from a considerable distance and reported it to Captain Darius Malott but in the confusion the Captain gave no orders until the Augusta was upon her. At the last minute the Captain yelled to the helmsman "Hard Up! For God's sakes, Man! Hard Up!" as the Augusta plunged into the side of the Lady Elgin just aft of her port paddlewheel.

The

Lady Elgin was making good time and careened on with the Augusta's bowsprit

buried deep in her side. The Augusta was pulled along with her for a short distance

and pried the Elgin's sidewheel and hull planking out as she turned in the water.

A few moments later the Augusta dislodged and the Elgin quickly pulled away.

Captain Malott and his crew were immediately concerned for their vessel and

believed that she must have sustained extensive damage below the waterline.

When they looked for the Elgin, they could no longer see her, causing Capt.

Malott to remark "That steamer sure got away from here in a hurry."

Believing they had struck the Elgin only a glancing blow, and now fearing they

might founder, the Augusta continued on for Chicago immediately.

The

Lady Elgin was making good time and careened on with the Augusta's bowsprit

buried deep in her side. The Augusta was pulled along with her for a short distance

and pried the Elgin's sidewheel and hull planking out as she turned in the water.

A few moments later the Augusta dislodged and the Elgin quickly pulled away.

Captain Malott and his crew were immediately concerned for their vessel and

believed that she must have sustained extensive damage below the waterline.

When they looked for the Elgin, they could no longer see her, causing Capt.

Malott to remark "That steamer sure got away from here in a hurry."

Believing they had struck the Elgin only a glancing blow, and now fearing they

might founder, the Augusta continued on for Chicago immediately.

Meanwhile, onboard the Lady Elgin, all was pandemonium. 50 head of cattle that had been in pens below deck were driven overboard in an attempt to lighten the vessel, and cargo including iron stoves was moved to the starboard side in order to raise the gaping hole in the Elgin's side out of the water. An attempt was made to launch one of the lifeboats, but it was lowered without being secured and had no oars. People watched helplessly as it drifted away from the vessel with only the First Mate and a few crew on board. Another lifeboat leaked so badly that it could not be used. Some alert coal shovelers spotted a mattress and tried to stem the flow of water by lodging it in the huge gash, but the water quickly pushed it aside. As the Elgin sank, she began to disintegrate and a split in her hull cut most passengers off from the life preservers. People began grabbing anything that would float and a crew of Irish Milwaukee firemen began chopping the hurricane deck off with axes in order to create a raft. Captain Wilson and others chopped doors down in order to rescue sleeping passengers. The Elgin sank stern first and the air rushing forward caused her upper works to explode as she broke up and sank. Within 20 minutes, the Lady Elgin had broke up and most of the vessel had gone to the bottom. Only her bow and two large sections of decking remained afloat. As the Elgin sank, a thunderstorm gathered and poured rain on the survivors with occasional flashes of lightning illuminating the horrific scene.

When

the light of dawn appeared over the horizon it revealed about 500 of the 700

or so passengers floating on various pieces of debris and decking. The lake

was very rough and the large deck sections began to break apart almost immediately

in the surging waves. Captain Wilson had taken charge of an infant and was sheltering

it from the rain and surge when he handed it to another survivor in order to

try and rig a sail. Just then, a large wave swept the child from the woman's

arms to its death. Two large hull sections with over 100 survivors on each remained

afloat for nearly five hours until they neared land. Fortunately, the water

was relatively warm and most survivors that found a piece of wreckage were able

to ride the 7 - 9 miles to the shallows. The First Mate's lifeboat was the first

to reach shore just below the bluff at Hubbard Woods. He scaled the massive

cliff and woke the Gage family who transmitted word of the disaster to Chicago

via the Chicago & Milwaukee railroad station. By 8:00 AM many student volunteers

from Northwestern University were on the scene as the wreckage and rafts approached

the shore.

When

the light of dawn appeared over the horizon it revealed about 500 of the 700

or so passengers floating on various pieces of debris and decking. The lake

was very rough and the large deck sections began to break apart almost immediately

in the surging waves. Captain Wilson had taken charge of an infant and was sheltering

it from the rain and surge when he handed it to another survivor in order to

try and rig a sail. Just then, a large wave swept the child from the woman's

arms to its death. Two large hull sections with over 100 survivors on each remained

afloat for nearly five hours until they neared land. Fortunately, the water

was relatively warm and most survivors that found a piece of wreckage were able

to ride the 7 - 9 miles to the shallows. The First Mate's lifeboat was the first

to reach shore just below the bluff at Hubbard Woods. He scaled the massive

cliff and woke the Gage family who transmitted word of the disaster to Chicago

via the Chicago & Milwaukee railroad station. By 8:00 AM many student volunteers

from Northwestern University were on the scene as the wreckage and rafts approached

the shore.

However,

the heavy seas had generated a massive surf with a powerful undertow just off

shore. When the frail rafts reached the breakers they immediately disintegrated,

pounding their human cargo into the water mercilessly. Perhaps as many as 400

survivors reached the shallows, but only 160 were saved, the remainder drowning

in the churning wreckage and surf. There were numerous acts of heroism on the

part of both rescuers and survivors. Captain Wilson was lost trying to save

two women from the surf when he was dashed on the rocks and killed just off

shore. His body was not found until three days later when it came ashore at

Michigan City, Indiana, some 60 miles away. Likewise, Captain Garrett Barry

of the Union Guards was also lost trying to save victims. He was drowned only

100 feet from shore when he succumbed from exhaustion. One of the several distinguished

people lost in the disaster was Herbert Ingraham, a member of the British Parliament

and owner of a London newspaper. Among the best known heroes of the Lady Elgin

disaster is Northwestern University student Edward Spencer. He is said to have

repeatedly charged back into the boiling surf to rescue people despite numerous

injuries from floating wreckage. In all he is credited with saving 18 people

after which he became delirious, repeatedly asking "Did I do my best?"

He was allegedly confined to a wheelchair for the rest of his life and was the

impetus for the establishment of the Evanston, Illinois US Lifesaving Station

which was henceforth manned by NWU students. A plaque in his honor at a Northwestern

University gymnasium commemorates his heroic effort. One survivor who reached

shore did so by riding in on the carcass of a dead cow while another climbed

into one of the Union Guards' bass drums and rode the waves to shore. Another

man climbed into a steamer trunk which is today on display at the Wisconsin

Marine Historical Society, and paddled it to shore. For

a list of known survivors and victims click here.

However,

the heavy seas had generated a massive surf with a powerful undertow just off

shore. When the frail rafts reached the breakers they immediately disintegrated,

pounding their human cargo into the water mercilessly. Perhaps as many as 400

survivors reached the shallows, but only 160 were saved, the remainder drowning

in the churning wreckage and surf. There were numerous acts of heroism on the

part of both rescuers and survivors. Captain Wilson was lost trying to save

two women from the surf when he was dashed on the rocks and killed just off

shore. His body was not found until three days later when it came ashore at

Michigan City, Indiana, some 60 miles away. Likewise, Captain Garrett Barry

of the Union Guards was also lost trying to save victims. He was drowned only

100 feet from shore when he succumbed from exhaustion. One of the several distinguished

people lost in the disaster was Herbert Ingraham, a member of the British Parliament

and owner of a London newspaper. Among the best known heroes of the Lady Elgin

disaster is Northwestern University student Edward Spencer. He is said to have

repeatedly charged back into the boiling surf to rescue people despite numerous

injuries from floating wreckage. In all he is credited with saving 18 people

after which he became delirious, repeatedly asking "Did I do my best?"

He was allegedly confined to a wheelchair for the rest of his life and was the

impetus for the establishment of the Evanston, Illinois US Lifesaving Station

which was henceforth manned by NWU students. A plaque in his honor at a Northwestern

University gymnasium commemorates his heroic effort. One survivor who reached

shore did so by riding in on the carcass of a dead cow while another climbed

into one of the Union Guards' bass drums and rode the waves to shore. Another

man climbed into a steamer trunk which is today on display at the Wisconsin

Marine Historical Society, and paddled it to shore. For

a list of known survivors and victims click here.

When

the Augusta reached port she was leaking badly and her bow was stove in. Captain

Malott was horrified to learn that the Lady Elgin had gone down. He promptly

gathered his entire crew and stated his case to shipping officials. He claimed

that the lighting configuration on the Elgin was incorrect and caused him to

misjudge her distance. He also stated that he believed that he only damaged

the Elgin's trim and feared for the safety of his struggling vesseland therefor

did not stop to render assistance. Public outcry against Captain Malott was

severe. The popular press attacked him as an agent of the Confederacy as well

as an agent of pro-Confederacy Britain where Captain Malott had spent some time.

Many felt that the ramming was deliberately planned to do away with the Union

Guards. Angry mobs gathered and the crew of the Augusta went into hiding. Captain

Malott was arrested and held for formal hearings. The Augusta herself was threatened

with burning and had a difficult time getting crews after the incident. Her

name was quietly changed to the Colonel Cook and she left the Lakes for the

Atlantic. She had a long career until she returned to the Lakes and was driven

ashore and wrecked near Cleveland, Ohio in 1894. Captain Malott and his crew

eventually found another vessel, the bark Mojave. In a questionable coincidence,

the Mojave disappeared without a trace almost four years to the day after the

Lady Elgin disaster. All but one of the crew lost on the Mojave had been on

the Augusta when she rammed the Lady Elgin and many though justice had been

served. The Mojave was thought to have foundered in northern Lake Michigan,

but it is possible that her crew was lynched in response to the Elgin disaster.

When

the Augusta reached port she was leaking badly and her bow was stove in. Captain

Malott was horrified to learn that the Lady Elgin had gone down. He promptly

gathered his entire crew and stated his case to shipping officials. He claimed

that the lighting configuration on the Elgin was incorrect and caused him to

misjudge her distance. He also stated that he believed that he only damaged

the Elgin's trim and feared for the safety of his struggling vesseland therefor

did not stop to render assistance. Public outcry against Captain Malott was

severe. The popular press attacked him as an agent of the Confederacy as well

as an agent of pro-Confederacy Britain where Captain Malott had spent some time.

Many felt that the ramming was deliberately planned to do away with the Union

Guards. Angry mobs gathered and the crew of the Augusta went into hiding. Captain

Malott was arrested and held for formal hearings. The Augusta herself was threatened

with burning and had a difficult time getting crews after the incident. Her

name was quietly changed to the Colonel Cook and she left the Lakes for the

Atlantic. She had a long career until she returned to the Lakes and was driven

ashore and wrecked near Cleveland, Ohio in 1894. Captain Malott and his crew

eventually found another vessel, the bark Mojave. In a questionable coincidence,

the Mojave disappeared without a trace almost four years to the day after the

Lady Elgin disaster. All but one of the crew lost on the Mojave had been on

the Augusta when she rammed the Lady Elgin and many though justice had been

served. The Mojave was thought to have foundered in northern Lake Michigan,

but it is possible that her crew was lynched in response to the Elgin disaster.

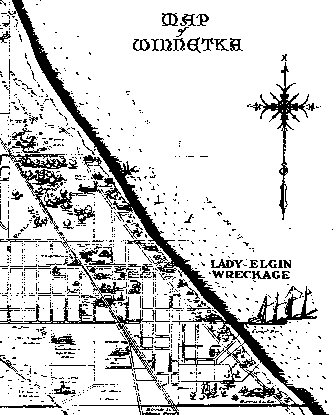

Bodies continued to wash up all around Lake Michigan well into December. Bodies were found as much as 80 miles from the wrecksite. Of the 430 or so confirmed lost, less than half were ever found. Many victims were unrecognizable and ended up in a mass grave at Winnetka. Others were returned to Milwaukee where many headstones still bear the inscription "Lost on the Lady Elgin." Because no official passenger list survived the tragedy, the exact number of passengers and victims will never be known. Many portions of the Elgin came ashore and were taken as souvenirs. A 100 ft. portion of her stern came ashore at Winnetka and was scavenged for years until it was removed and a large portion of her keel was used to construct an Evanston, Illinois barn which can still be seen. Her nameboard had been on display at the New Trier High School but disappeared some time ago. Other pieces of the Lady Elgin are still on display at historical societies around the area. The disaster was said to have orphaned over 1000 Milwaukee children and the entire city went into mourning over the tragedy. Most of the Union Guards were members of the Catholic St. John Cathedral in Milwaukee which continues to hold a memorial service for the Lady Elgin victims every September 8th to this day. Shortly after her loss, popular songwriter Henry C. Work penned the song "Lost on the Lady Elgin" which proved to be one of the most popular pieces of music over the next few years. Governor Randall of Wisconsin was cast as a villain in the Lady Elgin disaster for disarming the Union Guards and the incident served to further increase the tensions between Democrats and Republicans over the slavery and states' rights issues. An official inquest into the disaster exonerated both Captains, finding the rules of lakes navigation in effect at the time to be at fault. The Lady Elgin's bow remained afloat and drifted until her anchors dragged several miles off Winnetka. The upside down hull section remained a hazard to navigation for some time after the accident until it sank.

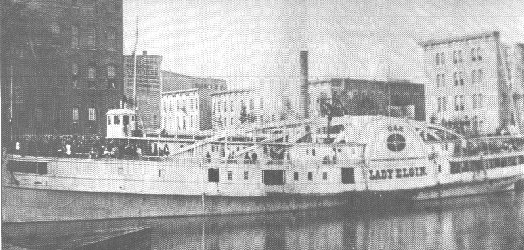

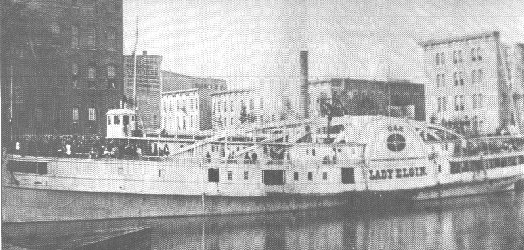

The

Lady Elgin was a double decked wooden sidewheel steamer built at Buffalo, New

York in 1851 by the well know ship chandlers Bidwell, Banta and Co. for Aaron

D. Patchin and Gillman D. Appleby of Buffalo. She was named for the wife of

Lord Elgin, the Governor General of Canada, and measured 252 ft. long by 33.7

ft. wide and 14.3 ft. deep. She carried 1037 gross tons beneath her decks and

her steam engine sported a 54 inch cylinder with an 11 foot stroke that powered

two 32 foot paddlewheels. The ship was built of white oak with frames with iron

reinforcements to carry 200 cabin passengers, 100 deck passengers, 43 crew and

800 tons of freight and subsequently would have been somewhat overloaded the

night of her loss. She was one of the larger steamers on the lakes and was very

popular due to her luxurious accommodations and quick speed. She had been built

to run between Buffalo, New York and Chicago, Illinois but had later been used

to take excursionists through the new Soo Locks to the Lake Superior wilderness.

The Lady Elgin was no stranger to accidents. On August 30, 1854 she was nearly

lost after punching a hole in her bottom on a large rock north of Milwaukee.

She was forced to run for Manitowoc, Wisconsin where she sank at the dock shortly

after arriving. She was again almost lost in a June 1858 gale on Lake Superior

when she was driven on the rocks while trying to enter Copper Harbor on Michigan's

rugged Keweenaw Peninsula. She was abandoned to the underwriters who had insured

her for $32,000. She remained high and dry until she was released on July 4,

1858. After extensive repairs totaling $8000 (a considerable sum at that time)

she was put back into service. However, she was nearly lost again in early August

of 1858 when she stranded on Lake Superior's Au Sable Point Reef, sustaining

$1400 in damages. She remained on the reef for two days until she was pulled

off by the steamer Illinois. Such was the life of an early Great Lakes steamer.

When finally lost, she was owned by Gordon S. Hubbard & Co. of Chicago and

was running primarily between Western Lake Michigan ports and Lake Superior.

The

Lady Elgin was a double decked wooden sidewheel steamer built at Buffalo, New

York in 1851 by the well know ship chandlers Bidwell, Banta and Co. for Aaron

D. Patchin and Gillman D. Appleby of Buffalo. She was named for the wife of

Lord Elgin, the Governor General of Canada, and measured 252 ft. long by 33.7

ft. wide and 14.3 ft. deep. She carried 1037 gross tons beneath her decks and

her steam engine sported a 54 inch cylinder with an 11 foot stroke that powered

two 32 foot paddlewheels. The ship was built of white oak with frames with iron

reinforcements to carry 200 cabin passengers, 100 deck passengers, 43 crew and

800 tons of freight and subsequently would have been somewhat overloaded the

night of her loss. She was one of the larger steamers on the lakes and was very

popular due to her luxurious accommodations and quick speed. She had been built

to run between Buffalo, New York and Chicago, Illinois but had later been used

to take excursionists through the new Soo Locks to the Lake Superior wilderness.

The Lady Elgin was no stranger to accidents. On August 30, 1854 she was nearly

lost after punching a hole in her bottom on a large rock north of Milwaukee.

She was forced to run for Manitowoc, Wisconsin where she sank at the dock shortly

after arriving. She was again almost lost in a June 1858 gale on Lake Superior

when she was driven on the rocks while trying to enter Copper Harbor on Michigan's

rugged Keweenaw Peninsula. She was abandoned to the underwriters who had insured

her for $32,000. She remained high and dry until she was released on July 4,

1858. After extensive repairs totaling $8000 (a considerable sum at that time)

she was put back into service. However, she was nearly lost again in early August

of 1858 when she stranded on Lake Superior's Au Sable Point Reef, sustaining

$1400 in damages. She remained on the reef for two days until she was pulled

off by the steamer Illinois. Such was the life of an early Great Lakes steamer.

When finally lost, she was owned by Gordon S. Hubbard & Co. of Chicago and

was running primarily between Western Lake Michigan ports and Lake Superior.

The Lady Elgin was forgotten by all but historical societies until the mid 1970s when salvor Harry Zych and others began to hunt for her remains, eventually finding them in 1989. Since then, a great deal of controversy has been generated regarding the Lady Elgin and Great Lakes shipwrecks in general. Zych had wanted to salvage artifacts from the wreck for a traveling display available to the non-diving public, while the State of Illinois (Illinois Historic Preservation Agency) claimed ownership and wanted the wreck and artifacts left on the bottom for archeological study. The ensuing court battles have been won alternatingly by both sides who continually appealed. In September of 1993 an agreement in which Zych donated the wreck to the Illinois Historic Preservation Agency was reached. However, in late 1994, Zych asked a judge to vacate that agreement, and the wreck is once again being contested. In 1996, Zych was awarded the wreck based on the premise that her insurers had never officially abandoned her. However, the State appealed and the case went to Federal Courts. In 1999, the case was finally resolved with Zych winning legal ownership of the Lady Elgin remains. Inevitably, the dubious wisdom of salvaging historical remains from Great Lakes wrecks has begun to emerge. As in the case of the 150 year old schooner Alvin Clark raised intact from Green Bay in 1969, divers are discovering that the public will not pay large sums of money to see rusty and decaying historical artifacts. The Clark rotted into the ground, eventually being bulldozed due to lack of interest. Today the States and Provinces surrounding the Great Lakes are discovering that thousands of divers will come to see a submerged wreck of almost any vintage and spend thousands of dollars to do it, while few people will pay much to see artifacts on the surface, no matter how historic. It is now illegal to remove artifacts from any Great Lakes shipwreck over 50 years old unless granted legal salvage rights, and all surrounding states and provinces enforce strict historic wreck conservation laws. A strong conservation ethic has also developed among Great Lakes divers, and very few now remove anything from historic wrecksites.

The Lady Elgin's existing remains lie today in four main wreckage fields, several

miles off Highwood, Illinois. The area of greatest interest is the vessel's

considerable bow section which had remained afloat for some time after the wreck.

It lies mostly broken in 60 ft. of water. Numerous artifacts including the ship's

anchor, chains and capstan remained in this area when the bow was discovered

and some were removed for public display by Harry Zych's non profit organization,

The Lady Elgin Foundation. Unfortunately, many articles were removed without

permission by unscrupulous divers and will probably never be seen again. The

visibility in the bow area is usually good and numerous photos have been taken

in the area. Some distance away from the bow is a debris field containing the

Lady Elgin's boiler which fell through the bottom of her hull when she broke

up. Another debris field reportedly contains remains of the Elgin's sidewheels,

but has never been documented. Other debris fields contain machinery, tools,

ship fittings and personal effects. The sites lie in 55 - 60 ft.of water and

have been cataloged in an archeological study by the Underwater Archeological

Society of Chicago. Private video documentaries have also been prepared by area

sport divers. Divers are not generally welcome to visit the wreckage sites of

the Lady Elgin without first obtaining permission from Harry Zych and the Lady

Elgin Foundation. Divers who do visit should treat the site with the same respect

as any other site on the National Register of Historic Places and leave artifacts

for others to see. There are at least three major wreckage fields from the Lady

Elgin, which are illustrated below. Although the location of the Lady Elgin

has been in public circulation for years, divers and charters who wish to visit

the Lady Elgin should contact Harry Zych at LadyElginFound@aol.com

before visiting the site. Other debris fields are said to exist within a mile

of the known wreckage. Despite all the legal wrangling, there is surprisingly

little left of this historic vessel. The site maps below show the existing wreckage

that has been surveyed to date. Click on the thumbnails for a larger view.

For the non-diver, the stretch of beach where the Elgin came ashore can be visited. Her wreckage made landfall over a five mile stretch from Winnetka to Evanston, Illinois. The main area where survivors and wreckage came ashore is shown on the inset map. Artifacts that have been retrieved by the Lady Elgin Foundation thus far include pre-Civil War muskets, swords, glassware, china, serving ware, a chandelier and the ship's whistle. The Chicago Historical Society, the Evanston and Winnetka Historical Societies and the Wisconsin Marine Historical Society hold many artifacts that were retrieved from shore after the wreck. Many excellent books can be purchased detailing the disaster as well as archeological reports and underwater video. Also for the non-diver, the annual September 8th Lady Elgin Memorial Cruise from Milwaukee visits the site of her wreck and usually includes a display of artifacts as well as interesting historical presentations.

For further reading on the Lady Elgin Disaster the following books are available and go into much greater detail:

Archeological Report on the USM Lady Elgin Wrecksite by the Underwater Archeological

Society of Chicago

Multimedia Presentation "Lady Elgin" by the Underwater Archeological

Society of Chicago (VHS Documentary)

The Lady Elgin Shipwreck - Captain Paul's Productions - VHS underwater documentary

by Paul Harju

Chicago's North Shore Shipwrecks by Mark S. Braun

True Tales of the Great Lakes by Dwight Boyer

Shipwrecks of the Lakes by Dana Thomas Bowen

Ships of the Great Lakes by James P. Barry

The Lady Elgin Disaster by Charles M. Scanlan (Out of print)

The Lady Elgin is Down by Pete Ceasar (Out of print)

Great Lakes Shipwrecks and Survivals by William Ratigan

History of the Great Lakes by John Brandt Mansfield (Out of print)

The Wreck of the Lady Elgin by Southport Video (VHS Documentary)

The USM Lady Elgin Shipwreck 1860 by Emmett Michael Jordan (Available on the

internet)

The following are among the best sources for original historical information and research into the Lady Elgin wrecksite and disaster:

Milwaukee Public Library, Herman Runge Collection

Institute for Great Lakes Research, Bowling Green State University

Great Lakes Historical Society, Vermilion, Ohio

Underwater Archeology Society of Chicago

Chicago Historical Society Collection

Illinois Historic Preservation Agency

The Lady Elgin Foundation

Harry Zych, American Diving & Salvage, Chicago, Illinois

Inland Seas (Various Issues) Journal of the Great Lakes Historical Society, Vermilion, Ohio

Winnetka Historical Society, Winnetka, Illinois

Evanston Historical Society, Evanston, Illinois

Rachel Carson Scuba Corps, Chicago, Illinois (Available on the Internet)

Paul Ackerman's Lake Michigan Dive Chart

Keweenaw Shipwrecks by Frederick Stonehouse

Dangerous Coast by Frederick Stonehouse & Dan Fountain

Rare photo of Lady Elgin at Chicago the day before the accident - Courtesy

of the Chicago Historical Society

Charcoal drawing of Augusta colliding with Lady Elgin - Courtesy of the Chicago

Historical Society

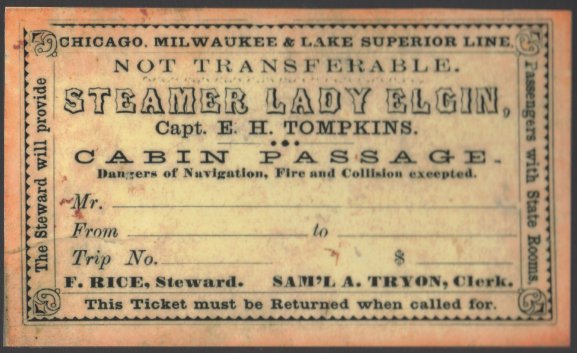

Lady Elgin Ticket for her last trip - Courtesy Harry Zych

Lady Elgin Ticket 1858 - Courtesy of the Great Lakes Shipwreck Research Foundation,

Inc.

Charcoal drawing of Sinking of the Lady Elgin - Courtesy of the Chicago Historical

Society

Woodcut of survivors on wooden raft - 1884 - Author's Collection

Woodcut of Schooner Augusta showing bow damage from the London Illustrated News

- Courtesy of the Wisconsin Marine Historical Society

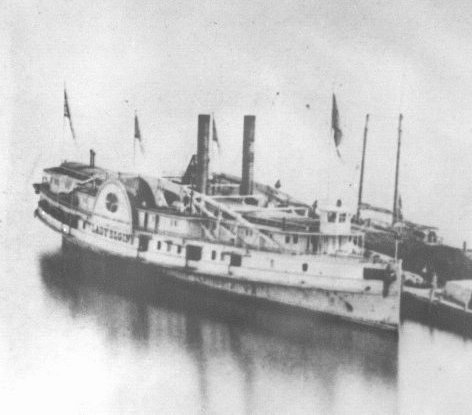

Rare photo of Lady Elgin at Northport, Michigan - Courtesy of the Institute

for Great Lakes Research

Archival Map of Winnetka Showing Lady Elgin Wreckage from Scanlan's Book

Underwater site maps of Lady Elgin remains - Courtesy Valerie Olson Van Heest

of the Underwater Archeology Society of Chicago

This article was originally prepared for the Wisconsin Veterans Museum - Military

History Sites Page.